[Time: 5 minutes. Read below or listen here.]

You don’t feel any guilt about the Bible? Really?

You don’t have the unpleasant feeling that you have not kept your commitment (New Year’s Resolution?) to read and study the Bible? You don’t think that by this time in your spiritual walk you should know much more of the Bible than you do? Have a Bible with lots of marks you’ve made in it but have never looked back at? That Bible on the table over there or on the shelf, it doesn’t whisper to you that you should be spending more time with it?

OK, maybe just a little guilt, right?

It’s not really your fault. Let me explain.

We have the misconception that, before Johannes Gutenberg’s creation of movable type in the mid 1400s and before the Reformation in the early 1500s, Christians were completely ignorant of the Bible. This is not historically accurate. In Western Europe and the British Isles not only were there regular and extensive daily public readings from the Bible in the churches, but society was filled with formal plays and informal street presentations based on stories from the Bible. A typical European of that era could likely do a better job of discussing the unfolding story of the Bible than a typical European or American could today.

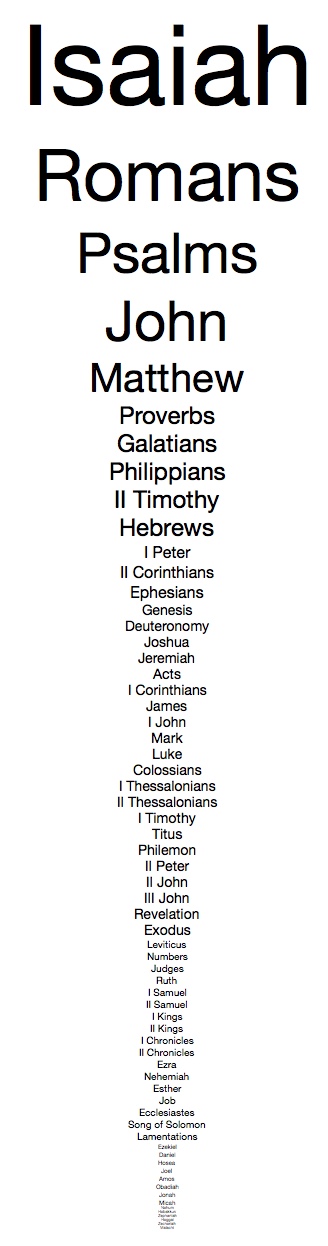

With the Reformation emphasis on the Bible and with hundreds of printing presses rolling out page after Bible page, why is our knowledge of the Bible so limited today, especially considering that you probably have multiple copies of this perennial best seller? The reason begins, quite unexpectedly, with Stephen Langton and Robert Estienne. Although the Old Testament had been divided into reading sections before the birth of Christ, no attempt to so divide the New Testament really took hold until Langston’s system of chapters about the year 1200 in England. And, it was not generally accepted for several hundred years. Gutenberg’s famous Bibles did not include chapter divisions. William Tyndale’s Bible was among the first to include chapter separations, but there were still no verses or verse numbers.

About 1550 a French printer and Greek scholar, Robert Estienne, wanted to create the first concordance for the Greek New Testament allowing scholars to more easily locate individual words and passages. He divided the entire Greek New Testament into verses, essentially the same versification used today. His system of verse numbers was an overnight success. The centers of the Reformation in Germany, France, Switzerland, England, and elsewhere seized on their new ability to quote individual Bible verses as proof texts and lob them at the Catholics and at each other.

Individual verses could be taken out of their contexts, removed from the story of the book of the Bible that gave them meaning, and used to prove doctrinal positions. Systematic theologies developed entirely based on harvesting proof texts to support propositions. A verse taken away from its context does not necessarily mean it is being misused, although it is certainly much easier to do so. But,from the Reformation on, Christians began focusing on individual verses, newly numbered and identified, as the basic unit of the Bible. This was a distraction during reading.

Compound the problem with today’s attitude that the Bible is really a self-help book full of our favorite supportive and encouraging verses, and it becomes almost impossible to read through any book of the Bible without subconsciously searching for the occasional verse that seems “just for me.”

No wonder most of us have a hard time reading more than a few verses or a chapter at a time. And, no wonder we feel a bit guilty about it.

Drop the guilt and read on to discover a better way to read the Bible.